|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| Torque-Power

Hi-Rise

Dual Plane Manifold

Design & Dyno Testing |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Given

the trend towards stroking, early-girl engines are screaming out for

specialist manifold treatment. Here's all you need to know. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

| |

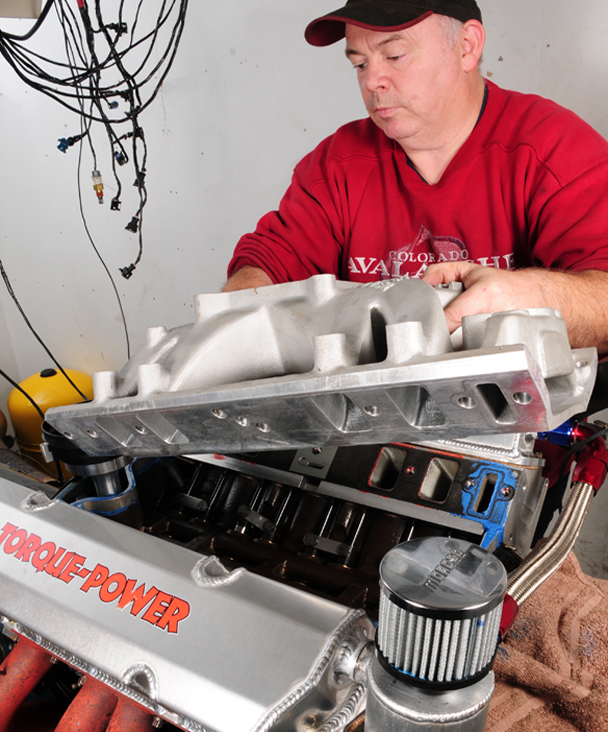

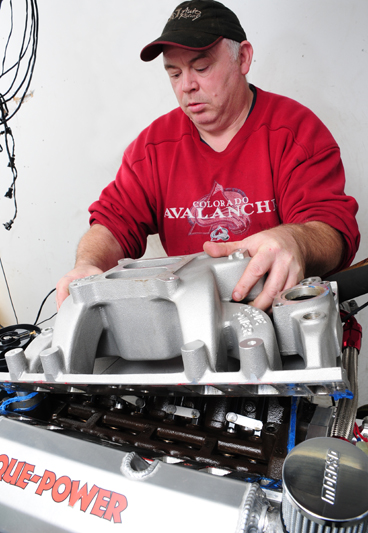

SPOILT

FOR CHOICE

Most

people who like earlier Commodores and even earlier Holdens will have

heard of Torque Power and the company’s products for Holden iron-block

V8 engines. In fact, we’ve covered most of them in the magazine

over the years. The high-rise dual-plane manifold shown here is the

latest development from the company. It was dyno tested at Micron Competition

Engines in Mount Gambier, SA and we went over to take a look.

Craig

Bennett, from Torque Power, suggests that for years there’s been

a gap in the product line available for the early configuration Holden

engine. “The manifolds that have been available for the engine

are pretty old designs, and were made primarily for standard displacement

308ci engines with ported iron heads,” he says. These days, however,

fresh build early Holdens are almost always stroked, commonly to 355ci.

He suggests that manifolds like the Torker and Performer, which work

fairly well on 308ci engines, don’t have the volume needed for

stroked versions.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

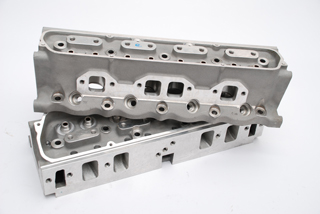

In

addition to manifolds, early design iron heads are also a restriction

when it comes to stroked engines. According to Craig, a 355ci engine

needs inlet runner volumes of about 160cc, but the ports in factory

iron heads can only be opened up to around 135-140cc before hitting

coolant. That’s why Yella Terra introduced its Dash 3 heads for

these engines. In collaboration with Micron, Torque-Power developed

performance port profiles for these heads some years ago and the designs

have been digitised for CNC replication. The modified ports have volumes

of 182cc which is enough to feed both 355ci and 383ci strokers. The

custom profiles are carved to order by Bullet Cylinder Heads in SA.

These

heads set the stage for stroked 383ci Holden engines capable of a fairly

easy 550hp when fitted with the single-plane Torque Power manifold shown

here, which we reviewed back in ‘05. In fact the single-plane

manifold was developed at the same time as the Dash 3 custom ports.

The thing is, this port/manifold combination is better suited to higher

revs and displacements than 355ci engines. The new dual-plane high-rise

manifold shown is matched to these smaller strokers with shorter duration

performance camshafts in the 230-255deg @ 0.050in range. The new manifold

doesn’t fall that far short of the single-plane on a 355ci at

the top end, but offers substantial gains in bottom end torque in such

applications.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| WHAT

IT TAKES

Torker

and Performer manifolds were designed to enhance performance but keep

carburettors below bonnet lines. For some people, this is an important

consideration but Craig says that it does introduce other compromises.

Airspeed, volume and general configuration are the fundamental considerations

in manifold design. Each affects the other and they must harmonize for

a manifold to work properly. Keeping a runner low reduces its length

and consequently its volume. Also, most importantly, it changes the

angle at which air enters the port and this in turn alters its behaviour

when it reaches the valve. To help visualize this, think of a manifold

runner as a simple length of straight pipe. It’s not hard to imagine

that altering the angle of the pipe in relation to the port would change

the flow characteristics of air within the port. Although a manifold

runner has a more complex shape, the same principle applies. Craig says

you can hear on the flow bench when the discharge angle of a manifold

runner is right or wrong.

The

cross sectional area of a manifold runner, and its taper, are the essential

factors in developing high airspeeds. Although increasing the cross

sectional area of a runner will increase its volume, it won’t

help get more air into an engine because airspeed will be reduced, particularly

at lower engine speeds. The high-rise design of the new dual-plane manifold

allows longer runner lengths. In turn, this allows adequate volume for

supplying a 355ci engine while maintaining a cross sectional areas conducive

to high airspeeds. |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

The

size and shape of the runners may be the main factors in controlling

airspeed into an engine, but they only partially control the overall

volume of a manifold. The volume of the central plenum has to be added

to that of the runners to get the true volume of a manifold. Altering

the size of the plenum allows changes to the overall volume of a manifold

without changing the airspeeds established by the configuration of the

runners. The high-rise design means that the plenum can be larger. The

resultant increase in volume contributes to feeding the larger displacement

of a stroker engine. What’s more, even though the plenum floor

is lower, it can still remain separate from the base of the manifold

and avoid contact with the hot oil splashing around in the valley.

THE

REAL WORLD

Testing

and developing on the flow bench is one thing but nothing beats dyno

testing because there are some things a flow bench just can’t

simulate. For a start, a flow bench sets up a continuous flow of air

through the manifold/head combination whereas the flow though an operating

engine is pulsed as the valves open and shut. Also, there’s no

fuel in the air passing through a flow bench. Craig says that the fuel

mist suspended in the air passing into an operating engine has greater

inertia than air alone, which makes it harder to get the mixture to

flow around bends. “You can get very close on a flow bench but

there’s no substitute for dyno testing”, he says.

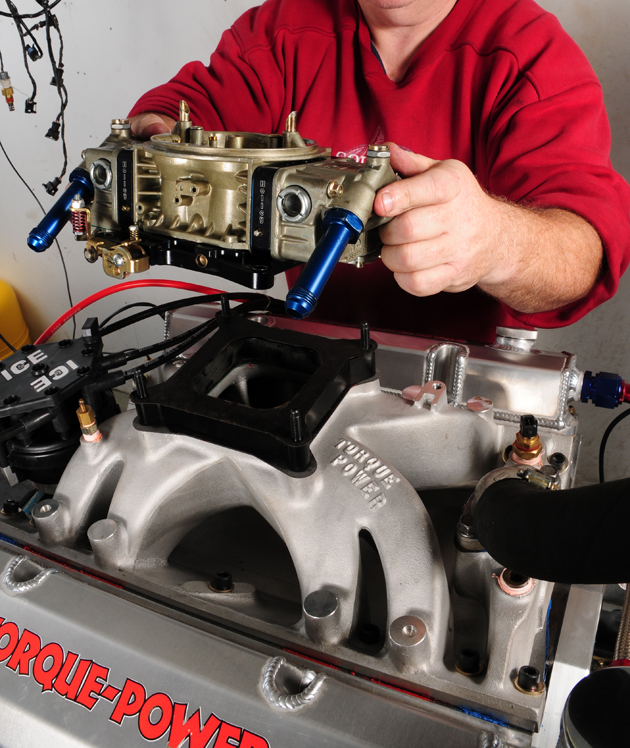

All of the tests were conducted using the one-inch spacer shown. Spacers

offer a quick means of changing the overall volume of a manifold to

suit a particular engine combination. Why not simply cast the extra

height into the manifold directly? Well, in many applications that don’t

need a spacer it would have to be machined off, which costs money. Also,

because spacers are available in a number of different sizes, different

manifold volumes can be tried quickly and easily.

They

also insulate carburettors from the hot manifold although the air-gap

styles shown here are less susceptible to that particular problem.

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

Basically, if a manifold/engine combination benefits from the addition

of a spacer it means that the design of the runners is probably good because

obviously they are able to pass more air. If the addition of a spacer

makes a combination go backwards, it’s odds-on that your combination

was fairly close to optimum. |

|

|

| |

If a spacer doesn’t make any difference at all, and flow testing

suggests that the combination should make more power, it means that

there’s a restriction somewhere after the plenum. It could be

anywhere but one of the first things to try would be another set of

exhaust pipes.

NO

APOLOGIES

As

we mentioned initially, the low profiles of the older manifolds shown

do keep carburettors from poking through bonnets. But a Holley on a

Torque-Power high-rise dual-plane will also clear the bonnet if it’s

fitted with a drop-profile air cleaner. However it’s tight so

you’d need to check your clearances carefully. Of course once

a spacer is added that’s no longer the case. Craig doesn’t

concern himself with this too much. “I made the manifold for performance”,

he said. The unwavering goal of optimising all aspects of the manifold

design for performance has paid off.

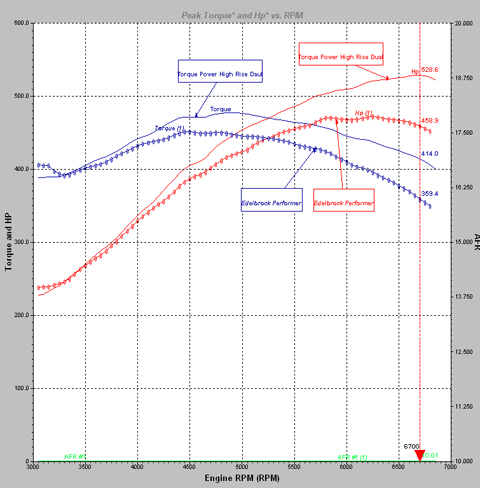

Over

a couple of days and many runs each manifold was put through its paces

on the Micron dyno. As the curves show, of the four manifolds tested

the Torque-Power single-plain high-rise made the most top-end power.

That’s not news. The single plane has been available for a few

years now and pretty much everyone knows that it’s a good thing.

Understandably, however, at lower revs it dropped below the other manifolds.

Again, this is exactly what you’d expect given that it’s

made for bigger engines turning faster. It’s also the reason that

the company developed the dual-plane, which makes more torque under

about 4250rpm. It must be said that the Performer does, too. However

above 4250rpm both Torque-Power manifolds leave the Performer behind.

The Torque-Power dual-plane has been designed for exactly this result.

In summary, it provides greater top-end power than other manifolds without

sacrificing torque at lower revs. This, of course, is the ultimate aim

of general performance tuning.

With

the introduction of this manifold there’s something for everyone

who wants to retain the port configuration of early Holden heads. But

which one to choose? In simple terms, a Performer dual-plane will suit

a standard displacement or 355ci engine with a cam in the 190-225deg

@ 0.050in range. The Torque-Power high-rise dual-plane is ideal for

feeding 308ci, 355ci and even 383ci engines with cams working in the

225-255deg @ 0.050in range. The Torque-Power high-rise single-plane

suits the stroked displacements with cams that work in the 255-280deg

@ 0.050in region.

|

|

|

| |

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| |

WANTS

AND NEEDS |

|

|

| Craig

says people commonly ring asking for a single-plane manifold. He asks

what they’re building and the answer is often a 355ci stroker with

something like a Crane 286 and pocket ported heads. They may have a 3800rpm

or 3500rpm converter or perhaps even a 2500rpm unit. He explains that

they don’t need the single-plane high-rise, the high-rise dual-plane

would better suit their needs. At the top end both manifolds will be within

about 10hp of each other but the dual plane will make perhaps 30-40 ft/lbs

more torque. The good thing about the extra torque is that it helps the

converter work better. This means that instead of running a 4200rpm or

4500rpm converter with a single-plane high-rise, a 3500rpm unit might

remain a workable proposition. And keep in mind that the less a converter

slips, the cooler your transmission fluid remains.

Previously, a person

with a 355ci stroker would have had to go to a high-rise dual-plane

if a 240deg @ 0.050in camshaft was used. Nothing else would allow the

cam to make the power it was capable of. However, as we’ve pointed

out, the single-plane is actually a bit too big for the combination

and would have reduced airspeeds too much for optimum results. This

new manifold addresses that issue and fills the gap in the range of

products available for the early motor. In our opinion, it’s definitely

worth a look. Craig is eager to point out that development of a product

like this is a collaborative effort and wouldn’t have been possible

without the efforts and assistance of all the companies mentioned. The

results of this united effort are available for $830 in either single

or dual-plane form.

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|